Motor oil or coconut oil, industrial silicone, biopolymers running hot inside a veterinary syringe and applied directly into the buttocks, legs, nose, or hip to meet the standard. Homemade injections in makeshift rooms, without anesthesia, without hygiene, botched surgeries, with no idea that the beauty they wanted could cost them their lives.

Since she was 13, Gretel looked for a body that matched her identity. Her transition was guided by what she could afford on her own and the urgency to find a face and a body that would make her feel at peace. But her search ended up becoming a surgical tragedy.

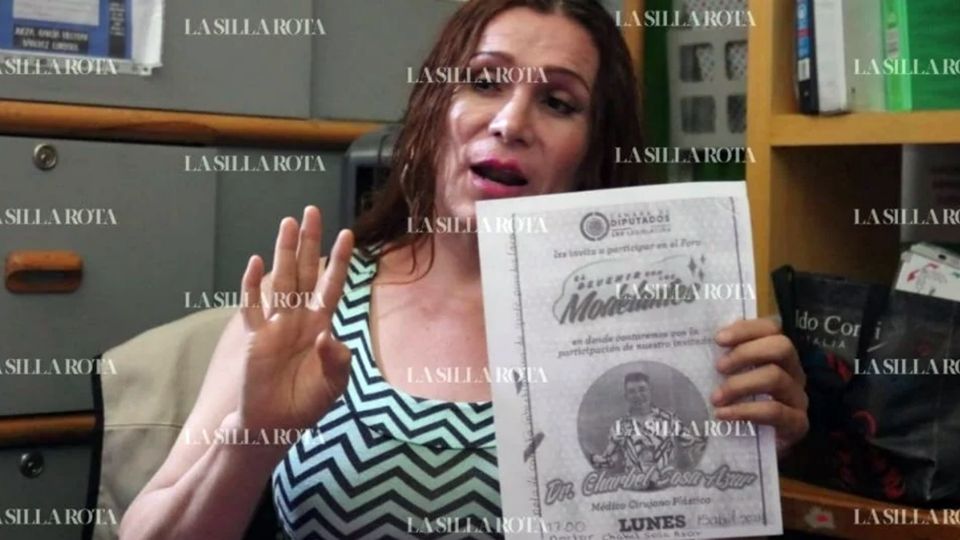

The procedure that was supposed to “beautify” her turned into irreversible harm. The doctor who operated on her, Charbel Andrés Sosa Azar, sliced off her nose, and the procedure left her barely able to breathe. Later he injected a substance into her nasal cavities that sealed off any possibility of airflow. Since then, her life depends on her mouth. She cannot close her lips to sleep. If she does, she suffocates.

Te podría interesar

The nights go by in fright: she wakes up gasping, hitting her chest, clinging to the idea of staying alive. Her nose is useless; her body, vulnerable; her work, destroyed. For her, the surgery not only weakened her health: it took away the way she earned a living and the presence with which she defended herself in the street.

She tried to seek justice. In 2005 she filed a complaint. The case never moved forward; it sank among desks, paperwork and pressure. And although public discourse boasts a Mexico City with cutting-edge policies for trans people, Gretel lives the contradiction: on one hand, rights announced in forums and documents; on the other, a system that leaves her adrift.

Nearly two decades after the harm, she still has no reconstructive surgery and no public institution has taken on her case. For Gretel, being beautiful ended up meaning losing her ability to breathe.

Context: In Mexico there is no official record of cases of women and trans women who have died from botched surgeries or from injecting body-shaping substances. The organization Brigada Callejera reports that in 2025 alone, around 150 have died and more than 300 have been treated. The most recent data from the National Medical Arbitration Commission (Conamed) reports more than 500 complaints related to the risks of unregulated procedures.

The rise of harm from “body-shaping substances”

In community work, Elvira Madrid, president of Brigada Callejera, explains that the organization has seen a drastic increase in complications from body-shaping substances among trans women.

They are currently accompanying more than 100 people who continue to wait for hospital care. This increase, she says, is related to the lack of access to specialized medical services and the persistence of clandestine procedures. She adds that the life expectancy of trans women is around 35 years—well below the national average.

According to Dr. Edith Cabrera, a general physician at the National Polytechnic Institute, the substances most commonly used in these clandestine interventions—and also the most dangerous—are industrial-grade liquid silicone, mineral oil, paraffin, polyacrylamide, and products marketed as “biogel” or “natural biopolymers,” which in reality are not.

She explains that all of them share a liquid or oily consistency, similar to a soft wax, which makes it easy for them to migrate throughout the body over time. That movement makes them especially harmful because they can shift into areas that cause chronic inflammation, systemic disorders, infections or progressive deformities, further complicating any later attempt at removal or repair.

COFEPRIS has documented that body-shaping substances cause severe infections, necrosis, organ damage, and permanent disfigurement. Added to that are chronic inflammatory reactions and autoimmune effects that continue to appear years later. Gretel is the face of that statistic: harm that does not end and repairs that never arrive.

To be beautiful, she paid with blows and fear

For Salma, beauty was never a whim; it was a desperate way to carve out a place in the world. But her story does not begin in an operating room—it begins on the street, where she works handing out flyers and where every day brings a new risk.

She injected biopolymers as a teenager, following what she then saw as beauty models among older trans women. They were thick substances, boiled oils, applied with ten-centimeter syringes without any control. What in her adolescence seemed like an instant miracle is today pain that does not stop.

When she sought support in the public health system, the response was an appointment eight months away. During that wait, the pain folded her over. Eight months she knew she wouldn’t survive. That is why she went to Brigada Callejera, where she does receive care.

Despite everything, Salma keeps going. She breathes halfway through poverty, violence and a body marked by interventions that never imagined such severe consequences. She believed beauty would give her freedom; she discovered it left her more exposed than ever.

For her, being beautiful meant surviving. And surviving, each day, becomes harder.

Living in pain for being beautiful

Sabrina now uses crutches. She looks at her legs, hips, arms, and she knows exactly where it hurts. She knows which areas burn inside, which throb in the early morning, which harden as if hot metal lived under her skin.

For years she has had oil injected into her calves, hips and arms. At the time she did it without thinking; beauty was urgent, a race against fear and discrimination. Today, every night, the price drives itself into her body.

The pain is unbearable. She wakes up because her calf burns, because her hip pulses, because the oil has shifted. She herself saw a 63-year-old friend inject her arms to “lift” them.

For Sabrina, being beautiful was not a luxury—it was a bet against the world. She boasts that she managed to have a body, but admits the price was far too high because today she wanders through hospitals that give her the runaround, she says, that don’t even have gauze; she struggles to get care and wonders why the government has left them alone.

Noemí always thought beauty was a door. A door to the modeling job she dreamed of. Anything that would take her out of those dawn hours cleaning tables and serving drinks. She was 22 when she decided to “fix herself a little.” She had no money, but someone told her she could do it with oil.

The first “fix” was with industrial oil, hot, loaded into a thick syringe that went straight into her chest. They told her it was normal for it to burn. That the lumps would settle on their own. That she shouldn’t worry if her skin became hard. Over time, the breast began to look deformed, but she carried on: she gathered money, saved for months, borrowed. She paid to “correct herself.” What they injected her with later also wasn’t what they promised.

In mid-2020 she felt a strange heat. Then a stabbing pain. It was very difficult for her to get medical attention because of the pandemic, and when she finally did, they told her the implant fluid had leaked and Noemí could not even lift her arm from the pain. They took her to Rubén Leñero Hospital, where she is still treated today. The daily dressings hurt. Her skin is irritated, inflamed, fragile. The doctors explained that the oil mixed with the shaping substances had deformed ducts. That real reconstruction would cost even more than what she already paid… and that it might not even be possible.

She lost her waitress job in the pandemic. Today she and her daughter run a hamburger stand in their neighborhood. “I tell her, no surgeries, no putting on a little breast or anything. I was dumb, look—one is dumb, really. If someone had told us that this really happened, none of us would have done it, or I don’t know—I don’t understand today why we want a body that costs us so much,” she adds.

These women all agree that the brutal demand to reach a beauty ideal has cost them dearly. The three paid for more feminine bodies, more “acceptable,” more “beautiful,” and today they are seeking medical care.

djh