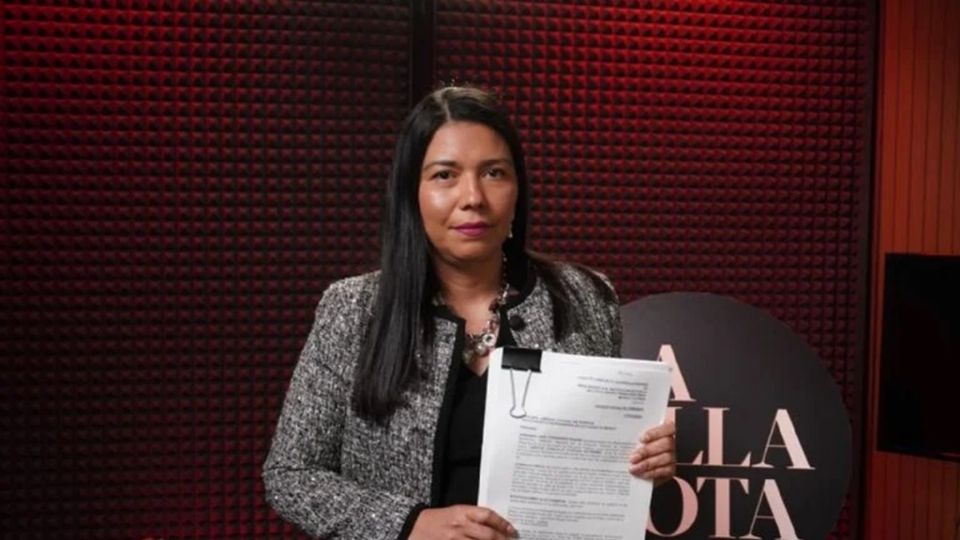

For ten years, Lizzette Cáceres’ work at BBVA México focused on preventing the bank from losing money in labor lawsuits. Today, the former executive maintains that she was wrongfully terminated after internally reporting multimillion-peso payments to former employees with ongoing labor cases and after experiencing workplace harassment for pointing out these alleged irregularities.

In January, Cáceres filed a claim before a Labor Court for wrongful termination and harassment. The case remains ongoing.

Safeguarding Bank Resources

Lizzette Cáceres joined BBVA in 2015, when the institution still operated under the BBVA Bancomer brand. Her last position was Labour Law Discipline Manager II within the legal-labor department. In that role, she explained, she oversaw the review and assignment of lawsuits filed by former bank employees across different regions of the country.

Te podría interesar

Her duties included coordinating case management with 18 external law firms, receiving notifications from labor authorities, and providing external counsel with the information required for the bank’s defense.

According to Cáceres, the work dynamic changed during the final six months before her dismissal, when BBVA launched an internal project aimed at closing a high volume of accumulated labor litigation.

Te podría interesar

At that time, the former executive estimates she managed around 500 lawsuits or complaints, many of which were reassigned to her direct supervisor, who joined the bank in 2021.

“She unilaterally decided that from that moment on she would personally take over those lawsuits and matters,” Cáceres said in an interview.

It was during this period that Lizzette detected what she describes as “serious anomalies.”

According to her testimony, after her supervisor assumed control of the cases, payments began to be authorized for the full claimed amount in files that did not have a final court ruling and, in some instances, where the amounts were allegedly overestimated.

Cáceres explained that prior to the project, payments were made in two ways: based on a final judicial ruling or through a settlement agreement supported by an external provider’s assessment of the risk of losing the case.

“The reality is that 100 percent was never paid without a judgment or resolution,” she emphasized.

However, she states that after her supervisor took control, cases were paid at 100 percent of their estimated value even when no court ruling existed.

She recalled approximately 25 cases in Acapulco valued at around 25 million pesos. She also cited a specific case in Tabasco in which, she said, one million pesos were paid to a worker who had signed a resignation and settlement agreement five years earlier.

“There was no longer any way for his claim to succeed, and even so, that one million pesos was paid,” she alleged.

The Beginning of Workplace Harassment

Cáceres said she raised her concerns directly with her supervisor. According to her account, the response was an angry rebuke. “She yelled at me and told me things had to be done her way because the project would move forward with or without me,” she stated.

From that moment on, Lizzette describes the beginning of systematic harassment.

She reported receiving an email accusing her of administrative errors and of failing to properly set aside financial reserves for payments. She also described constant phone calls outside working hours—between 7:00 and 8:00 p.m.—demanding urgent issuance of checks, as well as aggressive treatment and shouting.

She further alleges that her supervisor instructed external law firms to stop sending her information about the lawsuits, effectively isolating her from her duties.

Faced with this situation, Cáceres turned to institutional channels. She filed a formal complaint with the Compliance department and requested a meeting with the area’s director to present both the alleged financial irregularities and the harassment she was experiencing, invoking the bank’s integrity program known as “Oasis.”

READ ALSO: Mexican Cartels, a Factor of Political Destabilization in Latin America: Report

READ ALSO: What is Venezuela’s oil reform about, approved by the Chavistas

A Dismissal Without Full Severance

Rather than receiving an investigation or protection, she says the institutional response was her definitive dismissal.

Two weeks after reporting the situation, the director of Labor Relations informed her of her termination, arguing that “the environment had become too tainted” and that it would be her last day.

Cáceres recalls that the bank attempted to end the employment relationship with a financial offer below what the law provides for wrongful termination, which she rejected.

“My intention was always to defend the company’s interests because that had always been my commitment. We had a project called ‘Oasis’ that focused on integrity, and we were repeatedly told that if we saw misconduct we had the obligation to report it. That is what I did, but I was punished for it,” she concluded.

Following her dismissal, Lizzette filed a complaint for wrongful termination and harassment before the Tenth Federal Labor Court for Individual Matters, based in Mexico City.

READ ALSO: Navy removes commanders over fuel theft; four detained

READ ALSO: Greenland: Why Trump Argues It Is Important for U.S. Security

However, her case will, ironically, fall within the same area where she previously worked.

La Silla Rota requested a statement from BBVA’s communications department regarding these allegations and the internal complaint referenced by the former employee. As of the closing of this edition, the institution has not responded to the request for information.

VGB